A few weeks ago I wrote a piece on climate change and African vertebrates.

As I usually do, and especially in this case as Raquel had pointed the

paper out to me, I let her know that I'd written something and asked her

opinion. After quite a few emails back and forth we confirmed that I'd

misunderstood a figure in the paper that I'd thought was the crux of the

matter, but it turns out to have been not as useful at all.In light of

these discussions, Raquel and colleagues have now produced an addendum

to their paper that contains the figure I thought I was looking at and,

although I still have some issues with the work, it makes much more

sense to me now! In the interests of getting all this information out

there, as well as my pointing out the mistakes in the original post and

Raquel posting a comment there, I thought her ideas were valuable enough

to reprint in full from the comment as a new post, with some more

discussion here. So, here's what she has to say:

A blog about ecology of the savanna biome and other regions of interest to safari guides and visitors to East Africa.

Friday, 30 March 2012

Wednesday, 28 March 2012

On cattle in African protected areas

|

| Typical pastoralist scene near Lake Eyasi |

Monday, 26 March 2012

Why do savanna trees have flat tops?

|

| Umbrella Thorn, Serengeti: An icon of the savanna? |

It's an interesting question that was given some answers in a nice paper by Sally Archibald and William Bond who studied one species called the Sweet Thorn (Vachellia karroo) that, rather like some of our Vachellia species in East Africa exhibits a range of different growth forms in different habitats. In the semi-desert of the Karroo, it grows as a medium-sized ball of thorns, whereas in the savanna it has a fairly typical medium-tall flat-topped acacia look to it and in a forest it's a tall, thin tree. These differences are meditated mainly by genetic differences within the species, but equally could be caused in other species by a variable response to the environment - it's not really important to this discussion and, in fact, much of our discussion could focus on different species if we wanted. As always when we're thinking about what makes the savanna species, we'd be well advised to start with the savanna big four: nutrients, water availability, fire and herbivory.Now, the first two processes have impacts in all biomes, whereas it's the second two that are most distinctive about savanna and where we'll start our discussion.

Friday, 23 March 2012

Ecology for safari guides

This blog was set up originally to be a resource for safari guides around east Africa, and I hope it still fills that purpose. (We're coming up to 100 posts soon, so that might be a suitable moment to see how well we're doing...) Over the last couple of weeks we've been talking with a bunch of folk about forming a society for Interpretive Guides which could develop and maintain a qualification for guides in Tanzania - at the moment there's nothing widely recognised in the industry. With the assistance of the PAMS foundation, we're collecting syllabuses and guiding standards from around Africa and trying to develop something that may be seen as defining 'best practice' for guides in the region. As part of this process I've been putting together the things that I consider guides should know about ecology, and I thought it might be interesting to post the rough ideas I've got here for comments. There's much more that will go into the syllabus of course, this is just going to help contribute to the ecology module we're putting together, there's got to be lots more natural history modules in the course, covering mammals, birds, reptiles, plants and all the rest. And there's also likely to be as much about guiding ethics, psychology of groups, etiquette, etc., as well as the hard skills like proper driving, first aid and (if you're walking) firearms. So don't worry about those bits just now, I'm just doing the ecology bits.

Wednesday, 21 March 2012

Why is snake venom so toxic?

|

| Puff-adders probably cause more human snake-bites than any

other

African snake, but are rarely fatal. This is a juvenile, but don't think it's harmless. |

Monday, 19 March 2012

Distribution of Ethiopian Bush-crow and the nature of explanations

Yesterday I was sent a link to a press release from the excellent BirdLife International (read it here). It's talking about some research by an international team to try and explain the remarkably restricted range of the Ethiopian Bush-crow (cute picture here, since I've never actually been there to take my own), and in it, Paul Donald the lead author makes some interesting comments:

“The mystery surrounding this bird and its odd behaviour has stumped scientists for decades – many have looked and failed to find an answer. But the reason they failed, we now believe, is that they were looking for a barrier invisible to the human eye, like a glass wall. Inside the ‘climate bubble’, where the average temperature is less than 20°C, the bush-crow is almost everywhere. Outside, where the average temperature hits 20°C or more, there are no bush-crows at all. A cool bird, that appears to like staying that way.”

The reason this species is so completely trapped inside its little bubble is as yet unknown, but it seems likely that it is physically limited by temperature – either the adults, or more likely its chicks, simply cannot survive outside the bubble, even though there are thousands of square miles of identical habitat all around.

BirdLife International’s Dr Nigel Collar is co-author of the study. He added “Whatever the reason this bird is confined to a bubble, alarm bells are now ringing loudly. The storm of climate change threatens to swamp the bush-crow’s little climatic lifeboat – and once it’s gone, it’s gone for good.”

Tuesday, 13 March 2012

How do Kopjes form?

It's a question I regularly get asked by guides and also one that seems to bring a lot of google-searching visitors to the site, but I've not actually posted much of an answer yet although we have covered it briefly here, so here goes...

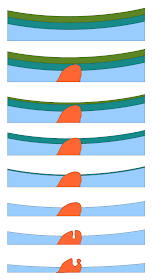

We start by remembering that Africa is old - most of the surface rocks are pretty ancient (and consequently washed clean of most nutrients - an issue we've talked about repeatedly). During these millenia, mountains have been formed and then worn down to small hills, whilst the valleys, plains lakes and seas have been buried in the sands and gravels of this erosion process. Over time and with immense pressure these sands and muds too have sometimes been 'recycled' into sandstones and mudstones in someplaces. It's not just been static though: later volcanic events sometimes push magma (un-errupted lava) through the layers of rock towards the surface where it cooled and formed an intrusion of new rock within a mass of older layers. (As shown in the diagram!)

|

| Cross-section through a kopje in the process of formation from smooth, uninterrupted landscape at the top to typical kopje at bottom, following millions upon millions of years of erosion. |

Monday, 12 March 2012

Why do birds sing in the morning?

|

| Ruppell's Robin-chat: an impressive mimic. Lake Duluti |

Thursday, 8 March 2012

Lewa Downs wildlife corridor really works!

As regular readers will have realised, I'm something of a sceptic about most things, and one of the things that I've been pretty sceptical about in the past is wildlife corridors. They sound like a great idea: wild spaces are increasingly fragmented (even here in East Africa), and as that process continues populations of plants and animals within these areas will become increasingly isolated from one another. Isolated and small populations are more likely to go extinct than large, well connected populations for a number of reasons ranging from inbreeding - in small populations you're rather more likely to have to mate with a brother or sister than in a large population, which can have serious genetic costs, to simply the risk of extreme events wiping everything out. So connecting those fragments with corridors along which animals can pass seems like a really good idea. Tiny experiments using micro-ecosystems where no-one cares if you isolate populations or connect them seemed to suggest that there might be something in this idea, and all of a sudden conservation corridors were high on the agenda.

As regular readers will have realised, I'm something of a sceptic about most things, and one of the things that I've been pretty sceptical about in the past is wildlife corridors. They sound like a great idea: wild spaces are increasingly fragmented (even here in East Africa), and as that process continues populations of plants and animals within these areas will become increasingly isolated from one another. Isolated and small populations are more likely to go extinct than large, well connected populations for a number of reasons ranging from inbreeding - in small populations you're rather more likely to have to mate with a brother or sister than in a large population, which can have serious genetic costs, to simply the risk of extreme events wiping everything out. So connecting those fragments with corridors along which animals can pass seems like a really good idea. Tiny experiments using micro-ecosystems where no-one cares if you isolate populations or connect them seemed to suggest that there might be something in this idea, and all of a sudden conservation corridors were high on the agenda. Tuesday, 6 March 2012

Nairobi bugs: WMD or Cancer cure?!

|

| 15 times more toxic than cobra venom, you really shouldn't eat a Nairobi beetle! |

There are actually at least two species of beetle known as Nairobi bugs around here, but they're so similar that most people won't notice them. Similarly marked relatives of these two are pretty widely distributed across the world, mainly in the tropics, and for now I don't think we need to bother about the precise identification. They're all small (7mm-1cm ish) and well marked with typical warning (aposematic) colours of black and red. In fact, despite the variety of names these are beetles (Coleopterans) of the family Staphylinidae, the rove beetles. If you don't know the Nairobi beetle, you might well know the Devil's Coach-horse and similar species - much larger and all black, but of a similar basic structure. The beetles we're interested in are of the genus Paederus and are carnivorous beetles that live mostly in long grass and anywhere with rotting leaves. And the most interesting things about them, as anyone will tell you, is that whilst they neither bite nor sting, they're still seriously nasty.

Sunday, 4 March 2012

Migrant bird population declines, an African perspective

|

| Willow warbler singing in Africa - 10g but probably headed to eastern Siberia... |

|

| Barred warblers are always a treat to see: headed to eastern Europe. |

Thursday, 1 March 2012

The role of termites in the savanna biome

|

| The ground is crawling with termites! Nr. Tarangire, Now 2011. |